I have visited twice the exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery, “Women Artists and Global Abstraction 1940-70”. This ambitious exhibition aims to celebrate abstract women artists of the mid-20th century and their role in shaping the art of their time.

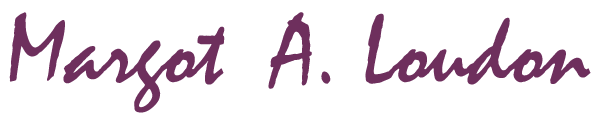

It is an overwhelming exhibition. Around a core of better-known American women painters and some western European artists swirl lesser-known names of women painters from across the globe. It was a steep learning curve and an important reminder that our knowledge of the art world is often still too blinkered. But grasping and appreciating the abstract tendencies from, I think, 80 artists variously from Japan, from the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and Australasia, and other countries, was daunting; this aspect alone merited a distinct exhibition. Furthermore it was frustrating not to know how their contemporary male artists were painting. I was on surer ground in this respect when I encountered the better-known names,, Lee Krasner who was Pollock’s wife, Gillian Ayres, and Lilian Holt who I learned was David Bomberg’s wife.

I also struggled with the arbitrary thematic approach. There were paintings in the nebulous section “Being, Expression, Empathy”, which could suitably have been included in the “Material and Process” category. The” Environment and Nature” section seemed to be curated to appeal to current sensibilities. Surely also some of the fine works in the gallery that purported to cover more intimate studies and paintings could have been “homed” under broader themes.

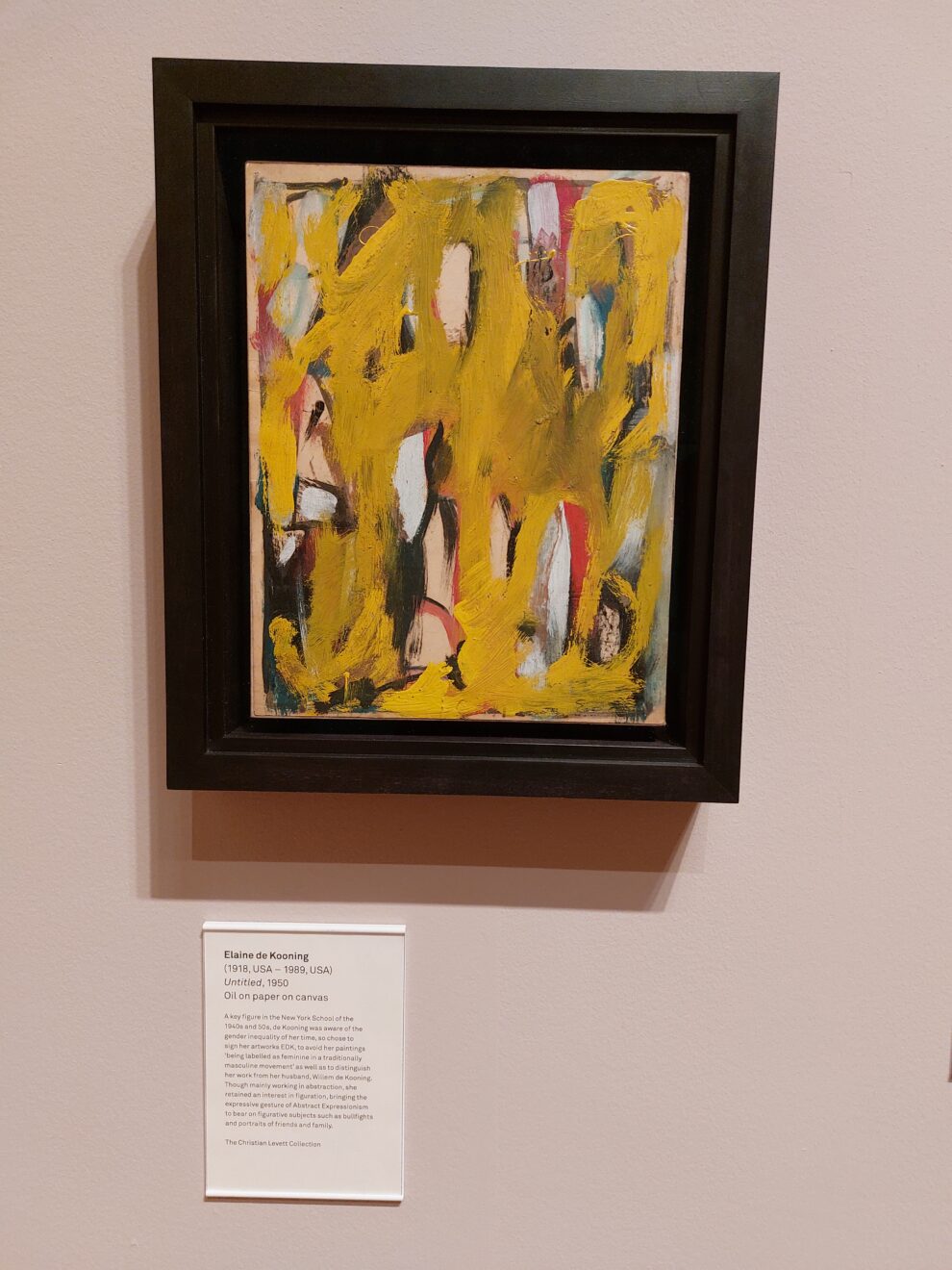

Despite these gripes I enjoyed much in the exhibition. It was a joy to see large fluid works by the pioneering Helen Frankenthaler, and to see how Lee Krasner maintained her own identity alongside her husband’s powerful work. Elaine de Kooning too. It was interesting to see Helen Shapiro’s early powerfully gestural paintings loosely based on Old Master works. Shapiro’s works are in the section “Performance, Gesture and Rhythm”. These tentative beginnings in which women artists began to realize a more physical event-based approach on the flat painting surface pointed the way to their using their own bodies as a creative force, the subject of the compact, focused exhibition in a separate gallery.

I was interested to learn that Betty Parsons was a painter herself as well as a gallery owner, and to see the early works of Gillian Ayres. I appreciated the work of artists I had not previously come across, too many.

Overall, the exhibition succeeded in showing that in the post-war years until the middle of the century, there was global enthusiasm for non-figurative art. I would agree that regional artistic heritage often melded with American and European influences to generate independent vital results. The role women artists played in a range of developments has been marginalized. However, I still think the contributions of the women artists to the different movements would have been clearer with a “less is more” focused approach.

My take-aways from this potpourri of works are that the essence of abstract works and those works hovering between abstraction and figuration, are materiality and process, gesture, and colour, and approaches that increasingly were to be driven by social, political and feminist concepts.