I visited the exhibition on Troy at the British Museum about the myths of Troy, and their interpretation and reinterpretation by artists over the millennia, with a dedicated explanation about the archaeological excavations at Hissarlik, the site identified in northern Turkey as the fabled city https://www.britishmuseum.org/exhibitions/troy-myth-and-reality

A modern installation comprising sculptures from Antony Caro’s Troy series and a Cy Twombly painting looking like a blood streaked sheet leads into the exhibition. The brutal, hard, barely figurative work of Caro, dramatically lit against a soundscape evoking the wind over the Trojan plain conveys the timelessness of the war story.

In the proto-myth, the “topless towers” of Troy were destroyed by Greeks after a 10 year war to restore the beautiful Helen to her husband Menelaus, king of Sparta. She had deserted him, fleeing to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris, his “prize” for choosing the goddess Aphrodite as the recipient of the golden apple. The brother of Menelaus, Agamemnon, king of Mycenae led the Greek army and gods and heroes fought and fell on both sides. The falling-out on the Greek side between Achilles and King Agamemnon and its aftermath, the deaths of Achilles’ friend Patroclus and of the Trojan Prince Hector, are the theme of the great epic poem, the Iliad. But the before, during, and after of this war yielded rich veins that have been mined by many poets and artists , to the present day.

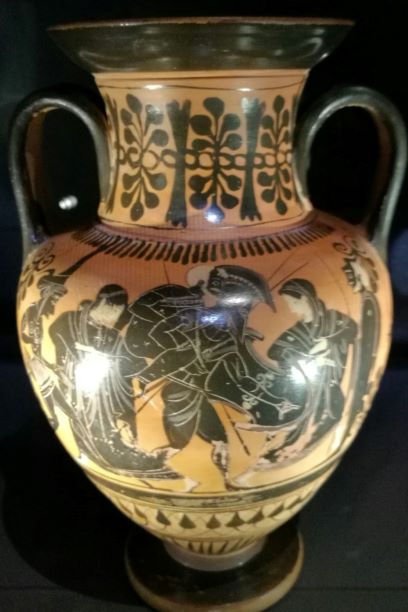

I have a strong personal interest in this exhibition. The subject of my PhD was the iconography of the destruction of Troy on Greek Attic black-figure vases, with particular emphasis on the escape, on the fateful night when the Greeks sacked the city, of the Trojan prince Aeneas carrying his aged father Anchises on his shoulders. The British Museum collection includes an amphora showing this scene shown in the exhibition.

Indeed, the early exhibition rooms exhibit a number of key pieces with which I am very familiar, beautifully displayed and providing clear explanations of the stories. The great epic poems, the Odyssey as well as the Iliad, are an important early source of key Trojan stories; initially in oral tradition they were probably turned into written form around the eighth century BCE. By the time the displayed vases were made and painted, the Trojan myths were being retold by other poets whose work is known only from fragmentary references. The vitality of the best vase painting is testament to the endurance of interest in the personalities of the war and their stories. There were later objects which I had not seen before. I think here of the two lovely Roman silver cups, dating from 30BCE-40AD, found in a grave in Hoby, Denmark.

The section on the excavations at Hissarlik remind us of the efforts of archaeologists to find Homer’s Troy but despite their aspirations and mistaken, romantic, interpretations notably of Heinrich Schliemann, no firm evidence has been found. Troy and its heroes, heroines and villains remain in the domain of artists who continuously interpret and reinterpret the stories.

I think the exhibition could have ended with the Hissarlik explanations. However, they lead on to a series of thematic displays comprising mediaeval and contemporary works reflecting the myths. I would have preferred the quality pieces, including the referencing of the harrowing adaptation of Euripides tragedy The Trojan Women by Syrian refugees, to have been incorporated in the earlier rooms. These thematic rooms finally did not do justice to the significance of the myth’s legacy.

In my printmaking, my classical education background has taken on a new life as I reference scenes from Greek pots in my own work. I have not yet drawn on the Trojan cycle, but perhaps I should.