This is a short musing on the pavilions I viewed in the Giardini, one of the two principal Biennale sites.

Unlike the flexible spaces for national displays in the Arsenale, the pavilions are historically established dedicated buildings, period pieces in their own right. Their distinctive architecture reflects the times in which they were built, ranging from the early years of the 20th century to just after the middle of the century. Given a longer time, I might have better appreciated how they looked from the outside and their architectural contexts, but my priorities drove me to the wealth of art within.

Installations, film, sculpture, paintings too, find their place in the different national homes. So many pavilions offered fascinating, some beautiful, others thoughtful and disturbing work.

In the Belgian pavilion the films of Francis Alÿs reflected on the pleasures children take in play and games, even when their lives are challenged by poverty and lack of resources. The films were insightful, moving and optimistic in their perceptions of childhood’s creativity.

I also have good memories of the American pavilion transformed by an impressive thatch into an African palace housing the marvellous sculptures and installations of Simone Leigh. Her work draws on African social and artistic heritage, reflecting on gender issues, race, colonization and the place of women in society. I loved the large sculptures.

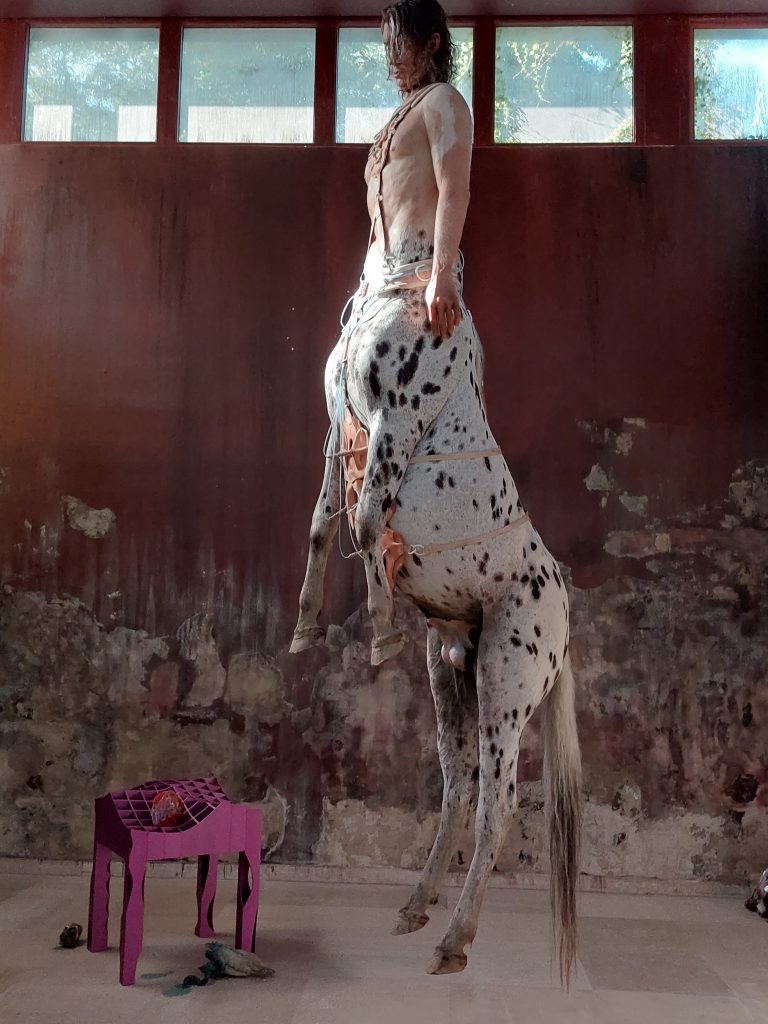

The Danish pavilion with the installation We walked the Earth by Uffe Isolotto. was haunting and disturbing. He showed an imagined future was of rural poverty and want inhabited by eerily realistic looking centaurs, hyperrealist renderings of surrealist hybrids. The male had committed suicide, the female was giving birth. The viewer could only speculate on what had led to this dystopian future.

Innovatively the Nordic pavilion had become the Sami pavilion examining their cultures, spiritual beliefs and place within the wider Scandinavia.

The Austrian pavilion was colourful. This stiking hybrid sculpture is a work of Jakob Lena Knebl.

The Korean pavilion was filled with gyrating, metamorphosing images and sculptures by Yunchul Kim. It is impossible to do justice in photographs to the shifting, restless world he creates.

Another pavilion stands out, the last pavilion of the day, the Greek. I suppose the installation by the artist and filmmaker Loukia Alavanou should be termed virtual reality, an experience, quite new to me. For 20 minutes I was plunged into a dystopian world , a participant rather than an observer of the last days of Oedipus’s rejection by society, as he wandered despised by all except his faithful daughter, Antigone. The ancient myth was linked to contemporary social issues, as the actors all came from Roma communities near Athens and the interpretation drew parallels between the treatment of Oedipus and the social restrictions placed on these communities. I shall long recall that immersive experience, caged with and physically recoiling from the fierce vultures, confronting the hatred of the chorus and most peculiar of all feeling like a disembodied head, as I skimmed along a desolate landscape by the seashore. I felt transformed into a surrealist image. Released from the experience, it took me a little while to get accustomed to terra firma.

However, after my Giardini pavilion visits, I was left with the nagging feeling that artists are outgrowing their traditional spaces. Maria Eichorn approached critically the German pavilion which cannot conceal its fascist connections, an inheritance of a 1938 redesign. In an otherwise empty space the artist has uncovered traces of the pre-1938 pavilion. Her artistic concept also included city tours to places of resistance and remembrance. Sadly that could not be followed-up but it made me think of the branch of the Situationist movement, which took art beyond gallery walls and linked cityscapes to experiences and memories. Artist Ignasi Aballi also questioned and reinvented the Spanish pavilion through the construction of new internal walls slightly skewed from the original walls, which modified the empty exhibition space and disrupted the viewer’s spatial comfort, history.