I visited the exhibition Three Generations of Japanese printmaking at the Dulwich Picture Gallery to get a better understanding of the woodblock printing tradition, and its development and to learn the story of this remarkable family, the Yoshidas.

The influence of Japanese prints on great western artists from the Edo period, by masters like Hokusai and Hiroshige and their contemporaries, was important but when Japan opened to the world, influences were eventually reciprocated. Western art while still influenced by the later Shin Hanga prints (literally new style) at the same time influenced Japanese art,

The story of the Yoshida family started with Hiroshi Yoshida active in the first part of the twentieth century. He travelled worldwide and his sightseeing inspired his image making. He imbued his painting and printmaking with principles of European art.

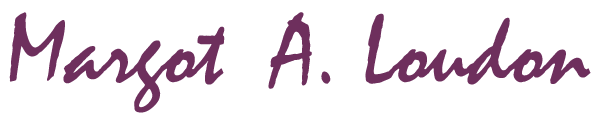

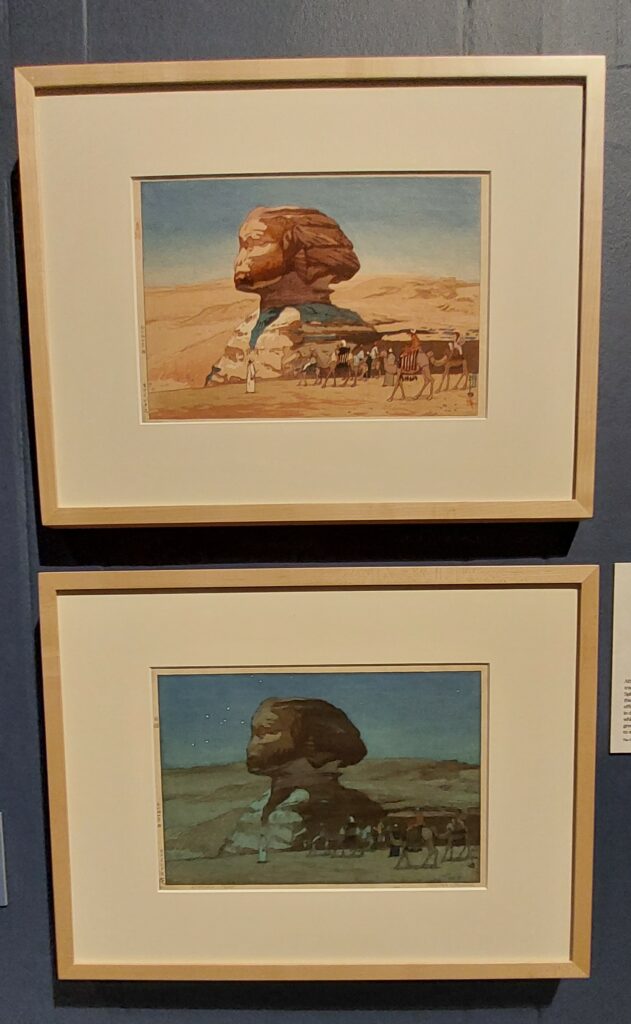

Among Hiroshi’s works showing his dexterity and creativity with the traditional woodblock technique are two views of the Sphinx one under a starry night and the second in bright day, perfectly showcasing his skills in rendering the qualities of light, shadow and dark. So many of his travel images are impressive. Equally the traditional Japanese scenes, some inevitably including cherry trees, are exquisite.

Sphinx

Kumoi Cherry Trees

I marvel at the depth and richness of colour and subtlety of tones obtained using plant and mineral-based watercolour inks on the woodblocks . Depending on the complexity of the scene, more than twenty blocks could be carved, each usually for a different colour.

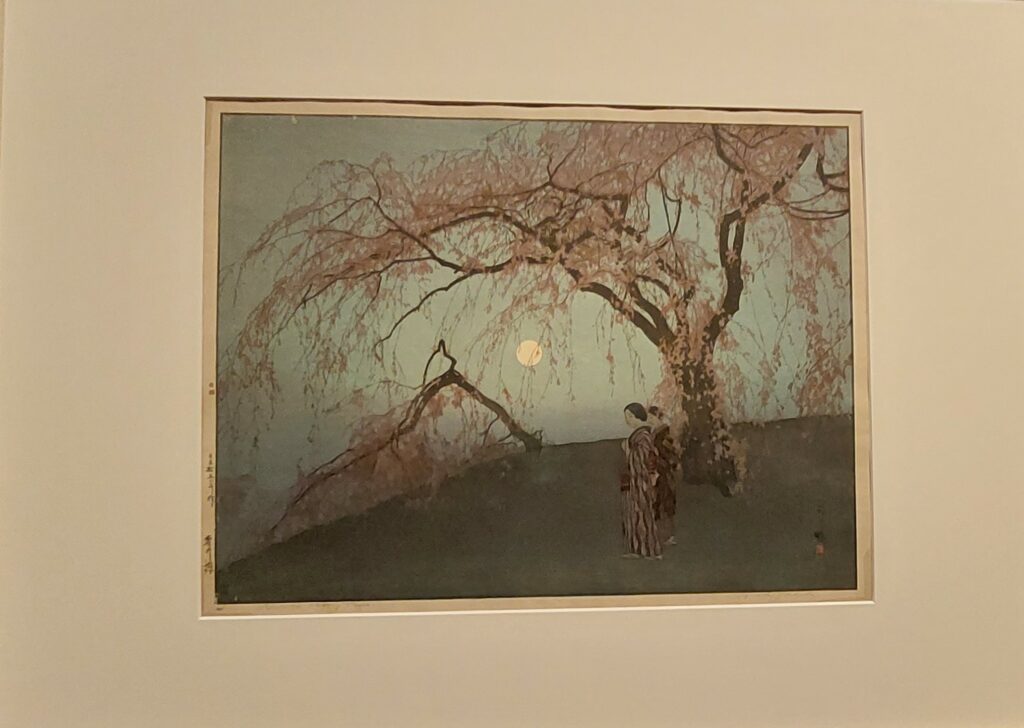

His sons, Toshi and Hodaka, carried on and simultaneously revolutionized the traditional techniques. They moved in step with worldwide artistic developments. Toshi continued to reprint and market his father’s works while his own work moved in radical directions. The semi-abstract Bruges reinvents the “floating world” of the earlier centuries. Other semi-abstracts evoke cityscapes and landscapes, retaining a characteristic serenity and harmony. His younger brother Hodaka was equally innovative and open to global art developments.

Bruges

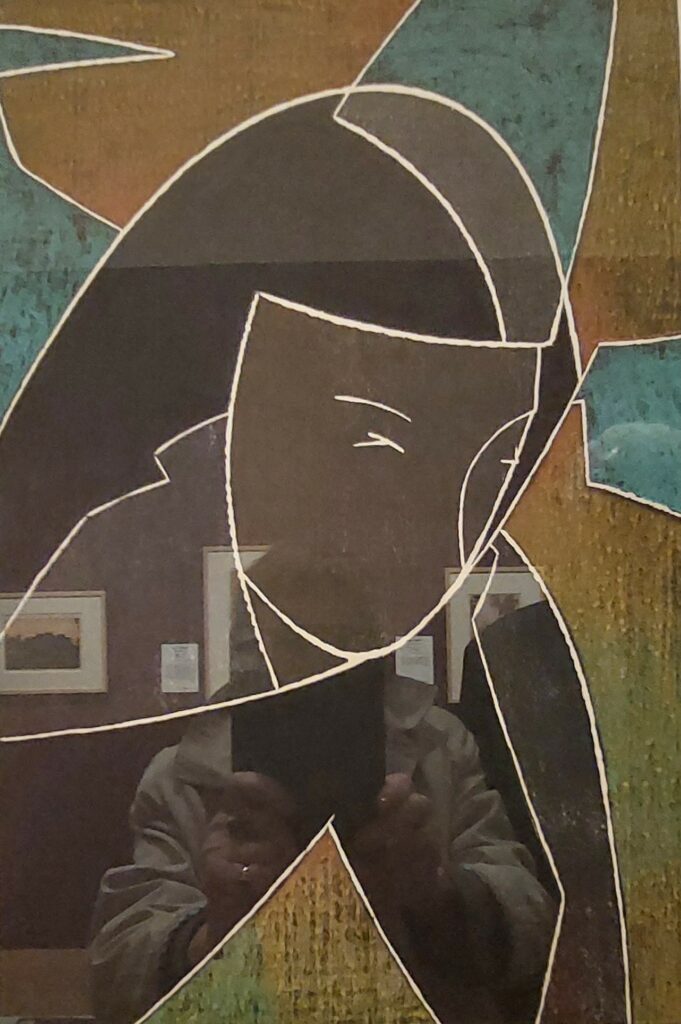

Woman in Baghdad

Some of Toshi’s works were not traditional woodblock prints but so-called white-line prints which involves precise application of colour on a single block. as seen on the deceptively simple Woman in Baghdad.

Hodaka’s early works are quiet toned abstracts. Later compositions reflected the Pop Art movement. As well as woodblock prints, he went on to produce monoprints using a range of materials, and also screen prints.

Woods

Flowering Kale, Gladiolus,Nasturtium,Red Canna, Iris, Yellow Iris

These beautiful works call to mind the works of Georgia O’Keefe but evolved from Fujio’s earlier nature and floral works.

The women of the family more than held their own in the artistic world while juggling family and business. Fujio, an established painter who married Hiroshi began experimenting with woodblock prints in the 1920s. At first her work was along traditional lines but by the 1950s she turned a series of her flower paintings into prints of beautiful sensuous close-ups of flowers. Perhaps she felt freer to move in a more radical direction after Hiroshi’s death in 1950.

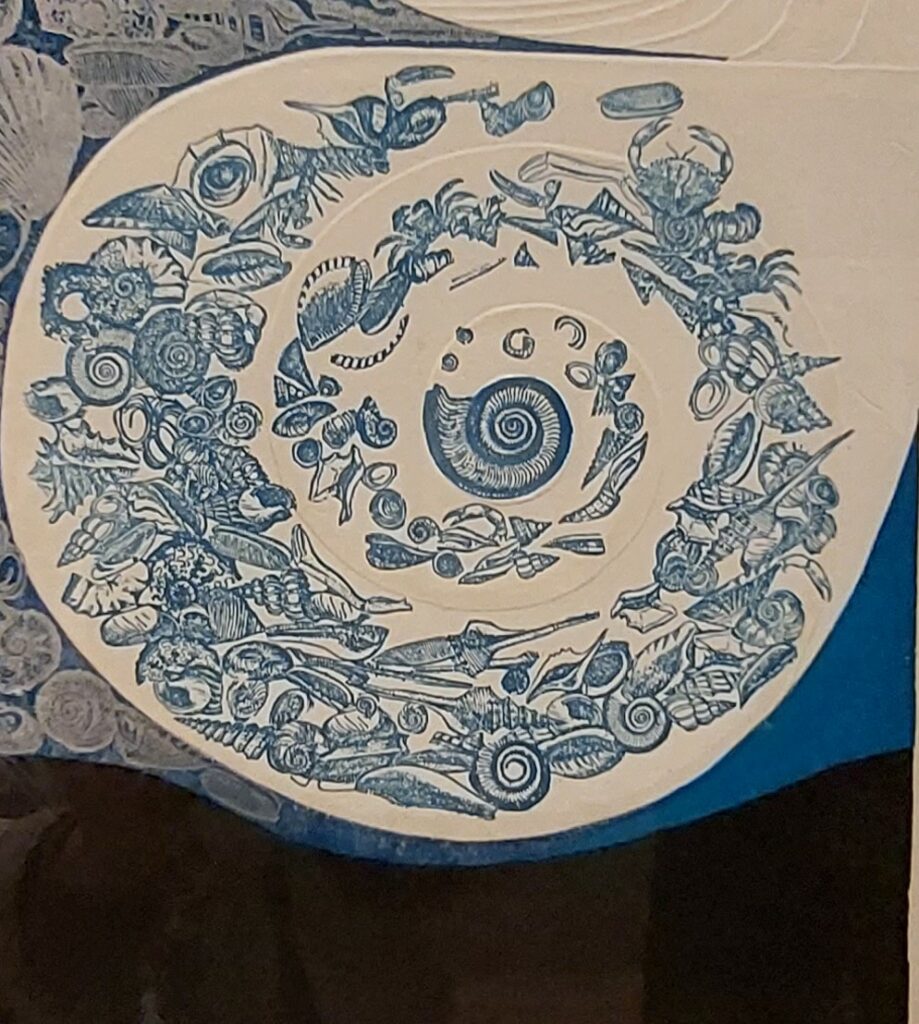

Hodaka like his father also married a gifted artist, Chizuko. Chizuko’s works morphed from stylized landscapes to rhythmical abstracts in which she explores geometric, subtly coloured and patterned spatial concepts to works influenced by her love of music and dance. She uses mixed techniques in her increasingly avant-garde work, variously combining woodblock printing with other techniques such as photo etching and embossing. Her work Reef C reflects her love of nature.. This woodblock print incorporating light embossing shows a delicacy that recalls fine lace.

Reef C

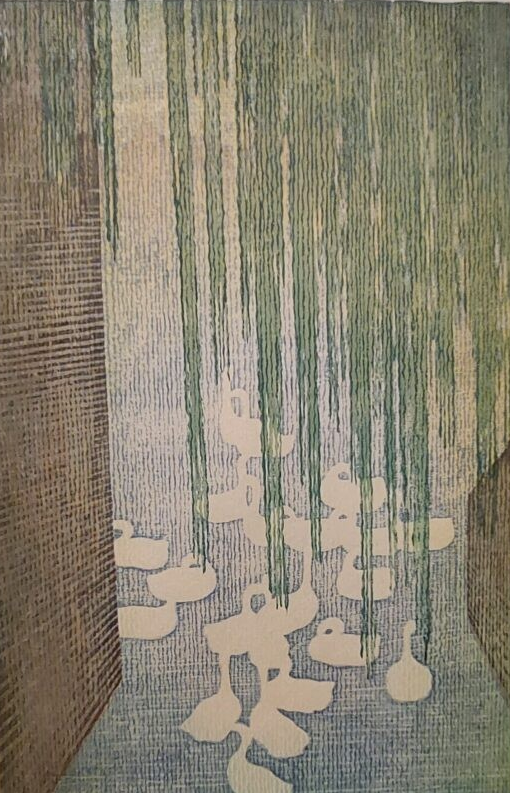

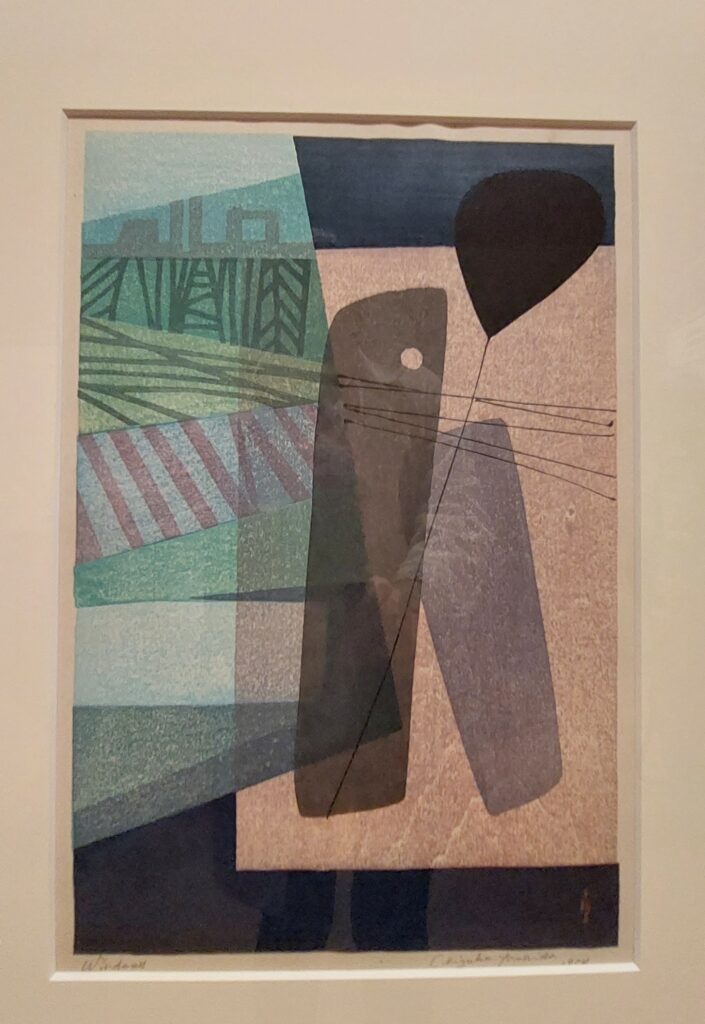

Windows

Ayomi, the representative of the third generation, Hodaka’s and Chizuko’s daughter, combines the traditional woodblock printing with silk screen printing to develop translucent, layered, large scale installations. Remarkably she trained as an architect with no intention to become an artist but drifted into an innovative approach to woodblock printing in a self-taught experimental way. In the last room of the exhibition the viewer is immersed in an installation specially created for Dulwich, Cherry Blossom, bringing us full circle.

My main takeaway was a confirmed admiration for the woodblock technique. I am not, however, going to try mokuhanga, its contemporary practice. Technically it would be too challenging. I am, nonetheless, already experimenting with more straightforward relief work on wood as I am attracted by the challenge of combining the grain of wood with the marks of the cutting tool. I would like to see more works by the family especially of the second generation with their readiness to experiment and innovate. I would like to learn more about the successful and well received work of the women in the family who defied my preconceptions of conventional female roles in twentieth century Japanese society.

The exhibition has been criticized for not showing us more historical context for the family’s work, and addressing the question of the extent to which Japan’s complex and painful militaristic and war years influenced their work. This question crossed my mind briefly when I saw the choice of themes pursued by Hiroshi in the Showa period, beautiful parks, gardens and temples. His work by then was probably reflecting changing and more conservative tastes in his customers. I did not, however, identify it as an issue for the other members of the family, in the prints on view. Like Hiroshi, his family were outward looking and loved travelling. They appreciated and explored different countries and cultures and were alert to global art movements. Like their country, they were ready to adapt to and thrive in a post war world.